Author Photo And Bio

1. Great Expectations by Charles Dickens (1860–61). Dickens gives a twist to an ancient storyline —of the child of royal birth raised in humble surroundings. Looking back on his life, Pip describes his poor youth near marshes in rural England —his chance encounter with a murderous convict, his experiences with the strange Miss Havisham, who always wears a wedding dress, and his love for her beautiful adopted daughter Estella. As he approaches adulthood, Pip learns that he has a secret benefactor who arranges opportunities for him in London, wherein lies the tale, and the twist.

1. Great Expectations by Charles Dickens (1860–61). Dickens gives a twist to an ancient storyline —of the child of royal birth raised in humble surroundings. Looking back on his life, Pip describes his poor youth near marshes in rural England —his chance encounter with a murderous convict, his experiences with the strange Miss Havisham, who always wears a wedding dress, and his love for her beautiful adopted daughter Estella. As he approaches adulthood, Pip learns that he has a secret benefactor who arranges opportunities for him in London, wherein lies the tale, and the twist.

2. The Trial by Franz Kafka (1925). The Trial is not just a book, but a cultural icon; Kafka is not just a writer but a mindset—“Kafkaesque.” Here, Everyman Josef K is persecuted by a mysterious and sadistic Law, which has condemned him in advance for a crime of which he knows nothing. Modern anxieties are given near-archetypal form in this parable that seems both to foretell the totalitarian societies to come and to mourn our alienation from a terrible Old Testament God.

2. The Trial by Franz Kafka (1925). The Trial is not just a book, but a cultural icon; Kafka is not just a writer but a mindset—“Kafkaesque.” Here, Everyman Josef K is persecuted by a mysterious and sadistic Law, which has condemned him in advance for a crime of which he knows nothing. Modern anxieties are given near-archetypal form in this parable that seems both to foretell the totalitarian societies to come and to mourn our alienation from a terrible Old Testament God.

3. The Man Who Loved Children by Christina Stead (1940). Stead said that writing this novel “was like escaping jail,” and one feels that great cathartic sweep as the dark side of family life unreels through astonishing scenes pitting Sam Pollit, the egotistical father “who loves children,” against his wife Henny, a household hetaera subject to rages, or his fourteen-year-old daughter Louisa, a precocious, hulking girl whose break for freedom crowns the book. Though this novel is semiautobiographical, Stead transforms personal revenge against her own outsized father into revelation.

3. The Man Who Loved Children by Christina Stead (1940). Stead said that writing this novel “was like escaping jail,” and one feels that great cathartic sweep as the dark side of family life unreels through astonishing scenes pitting Sam Pollit, the egotistical father “who loves children,” against his wife Henny, a household hetaera subject to rages, or his fourteen-year-old daughter Louisa, a precocious, hulking girl whose break for freedom crowns the book. Though this novel is semiautobiographical, Stead transforms personal revenge against her own outsized father into revelation.

4. The Red and the Black by Stendhal (1830). Stendhal inaugurated French realism with his revolutionary colloquial style and the famous pronouncement, “A novel is a mirror carried along a highway.” Julien Sorel, the tragic antihero, rises from peasant roots through high society. In his character, the “red” of soldiering and a bygone age of heroism vies with the “black” world of the priesthood, careerism, and hypocrisy.

4. The Red and the Black by Stendhal (1830). Stendhal inaugurated French realism with his revolutionary colloquial style and the famous pronouncement, “A novel is a mirror carried along a highway.” Julien Sorel, the tragic antihero, rises from peasant roots through high society. In his character, the “red” of soldiering and a bygone age of heroism vies with the “black” world of the priesthood, careerism, and hypocrisy.

5. A Dance to the Music of Time by Anthony Powell (1951–75). Powell’s panoramic series of twelve freestanding novels, grouped in four “movements,” charts the careers of four public-school friends from 1921 to 1971 against the backdrop of rapidly changing London. Built mosaic-like from many intimate, seemingly inconsequential encounters and scenes, the narrative moves with the pace, prismatic glitter, and cumulative force of a glacier, sweeping along sex, art, business, politics, and values in its wake. Devotees, who consider Powell to be England’s answer to Proust, praise the elegant style, intricate plotting, and above all the masterly characterizations, in a work that encompasses comedy, tragedy, and realism.

5. A Dance to the Music of Time by Anthony Powell (1951–75). Powell’s panoramic series of twelve freestanding novels, grouped in four “movements,” charts the careers of four public-school friends from 1921 to 1971 against the backdrop of rapidly changing London. Built mosaic-like from many intimate, seemingly inconsequential encounters and scenes, the narrative moves with the pace, prismatic glitter, and cumulative force of a glacier, sweeping along sex, art, business, politics, and values in its wake. Devotees, who consider Powell to be England’s answer to Proust, praise the elegant style, intricate plotting, and above all the masterly characterizations, in a work that encompasses comedy, tragedy, and realism.

6. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll (1865). Young Alice follows a worried, hurrying White Rabbit into a topsy-turvy world, where comestibles make you grow and shrink, and flamingoes are used as croquet mallets. There she meets many now-beloved characters, such as the Mad Hatter, the Cheshire Cat, and the Queen of Hearts, in this linguistically playful tale that takes a child’s-eye view of the absurdities of adult manners.

6. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll (1865). Young Alice follows a worried, hurrying White Rabbit into a topsy-turvy world, where comestibles make you grow and shrink, and flamingoes are used as croquet mallets. There she meets many now-beloved characters, such as the Mad Hatter, the Cheshire Cat, and the Queen of Hearts, in this linguistically playful tale that takes a child’s-eye view of the absurdities of adult manners.

7. The Black Prince by Iris Murdoch (1973). Bradley Pearson is a fifty-eight-year-old tax inspector who has written three books. Convinced he has a masterpiece within him, he quits his job and rents a tranquil cottage. His plan is thwarted at every turn, however, by the needs of his ex-wife, quarreling friends, his sister’s suicide, writer’s block, and his sudden passion for his friends’ twenty-year-old daughter. A murder caps off this philosophical thriller about marriage, love, and art.

7. The Black Prince by Iris Murdoch (1973). Bradley Pearson is a fifty-eight-year-old tax inspector who has written three books. Convinced he has a masterpiece within him, he quits his job and rents a tranquil cottage. His plan is thwarted at every turn, however, by the needs of his ex-wife, quarreling friends, his sister’s suicide, writer’s block, and his sudden passion for his friends’ twenty-year-old daughter. A murder caps off this philosophical thriller about marriage, love, and art.

8. New Grub Street by George Gissing (1891). One of the earliest examples of English naturalism, this grim chronicle of literary life in late-Victorian London bitterly portrays its author’s own struggles to live from his writing. In contrasting dedicated artist Edwin Reardon’s commercial failure with superficial romancer Jasper Milvain’s popular success, Gissing pointedly skewers the distorted values of the marketplace, while tirelessly enumerating the many forces working against artistic purity and sincerity. The novel is a diatribe, yet lucid characterizations (particularly that of Reardon’s depressed, demanding wife) and raw accusatory intensity give it a claustrophobic, nagging power.

8. New Grub Street by George Gissing (1891). One of the earliest examples of English naturalism, this grim chronicle of literary life in late-Victorian London bitterly portrays its author’s own struggles to live from his writing. In contrasting dedicated artist Edwin Reardon’s commercial failure with superficial romancer Jasper Milvain’s popular success, Gissing pointedly skewers the distorted values of the marketplace, while tirelessly enumerating the many forces working against artistic purity and sincerity. The novel is a diatribe, yet lucid characterizations (particularly that of Reardon’s depressed, demanding wife) and raw accusatory intensity give it a claustrophobic, nagging power.

9. Tristram Shandy by Laurence Sterne (1759–67). Sterne promises the “life and opinions” of his protagonist. Yet halfway through the fourth volume of nine, we are still in the first day of the hero’s life thanks to marvelous digressions and what the narrator calls “unforeseen stoppages”—detailing the quirky habits of his eccentric family members and their friends. This broken narrative is unified by Sterne’s comic touch, which shimmers in this thoroughly entertaining novel that harks back to Don Quixote and foreshadows Ulysses.

9. Tristram Shandy by Laurence Sterne (1759–67). Sterne promises the “life and opinions” of his protagonist. Yet halfway through the fourth volume of nine, we are still in the first day of the hero’s life thanks to marvelous digressions and what the narrator calls “unforeseen stoppages”—detailing the quirky habits of his eccentric family members and their friends. This broken narrative is unified by Sterne’s comic touch, which shimmers in this thoroughly entertaining novel that harks back to Don Quixote and foreshadows Ulysses.

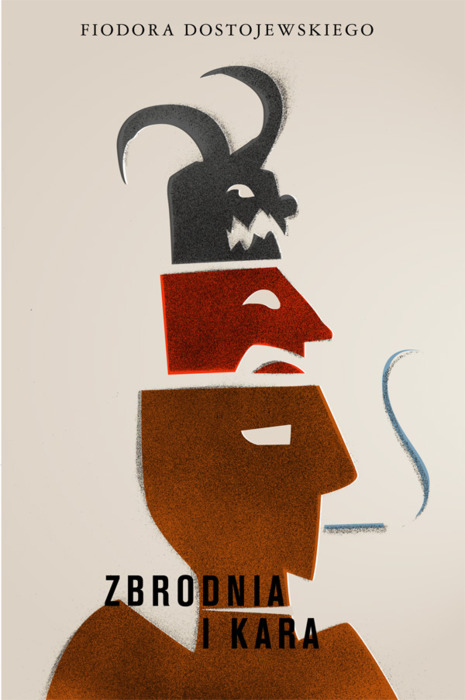

10. Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky (1866). In the peak heat of a St. Petersburg summer, an erstwhile university student, Raskolnikov, commits literature’s most famous fictional crime, bludgeoning a pawnbroker and her sister with an axe. What follows is a psychological chess match between Raskolnikov and a wily detective that moves toward a form of redemption for our antihero. Relentlessly philosophical and psychological, Crime and Punishment tackles freedom and strength, suffering and madness, illness and fate, and the pressures of the modern urban world on the soul, while asking if “great men” have license to forge their own moral codes.

10. Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky (1866). In the peak heat of a St. Petersburg summer, an erstwhile university student, Raskolnikov, commits literature’s most famous fictional crime, bludgeoning a pawnbroker and her sister with an axe. What follows is a psychological chess match between Raskolnikov and a wily detective that moves toward a form of redemption for our antihero. Relentlessly philosophical and psychological, Crime and Punishment tackles freedom and strength, suffering and madness, illness and fate, and the pressures of the modern urban world on the soul, while asking if “great men” have license to forge their own moral codes.