Author Photo And Bio

1. Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray (1847–48). The subtitle is “A Novel Without a Hero,” and never was a hero more unnecessary. In Becky Sharp, we find one of the most delicious heroines of all time. Sexy, resourceful, and duplicitous, Becky schemes her way through society, always with an eye toward catching a richer man. Cynical Thackeray, whose cutting portraits of society are hilarious, resists the usual punishments doled out to bad Victorian women and allows that the vain may find as much happiness in their success as the good do in their virtue.

1. Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray (1847–48). The subtitle is “A Novel Without a Hero,” and never was a hero more unnecessary. In Becky Sharp, we find one of the most delicious heroines of all time. Sexy, resourceful, and duplicitous, Becky schemes her way through society, always with an eye toward catching a richer man. Cynical Thackeray, whose cutting portraits of society are hilarious, resists the usual punishments doled out to bad Victorian women and allows that the vain may find as much happiness in their success as the good do in their virtue.

2. Tristram Shandy by Laurence Sterne (1759–67). Sterne promises the “life and opinions” of his protagonist. Yet halfway through the fourth volume of nine, we are still in the first day of the hero’s life thanks to marvelous digressions and what the narrator calls “unforeseen stoppages”—detailing the quirky habits of his eccentric family members and their friends. This broken narrative is unified by Sterne’s comic touch, which shimmers in this thoroughly entertaining novel that harks back to Don Quixote and foreshadows Ulysses.

2. Tristram Shandy by Laurence Sterne (1759–67). Sterne promises the “life and opinions” of his protagonist. Yet halfway through the fourth volume of nine, we are still in the first day of the hero’s life thanks to marvelous digressions and what the narrator calls “unforeseen stoppages”—detailing the quirky habits of his eccentric family members and their friends. This broken narrative is unified by Sterne’s comic touch, which shimmers in this thoroughly entertaining novel that harks back to Don Quixote and foreshadows Ulysses.

3. Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert (1857). Of the many nineteenth-century novels about adulteresses, only Madame Bovary features a heroine frankly detested by her author. Flaubert battled for five years to complete his meticulous portrait of extramarital romance in the French provinces, and he complained endlessly in letters about his love-starved main character — so inferior, he felt, to himself. In the end, however, he came to peace with her, famously saying, “Madame Bovary: c’est moi.” A model of gorgeous style and perfect characterization, the novel is a testament to how yearning for a higher life both elevates and destroys us.

3. Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert (1857). Of the many nineteenth-century novels about adulteresses, only Madame Bovary features a heroine frankly detested by her author. Flaubert battled for five years to complete his meticulous portrait of extramarital romance in the French provinces, and he complained endlessly in letters about his love-starved main character — so inferior, he felt, to himself. In the end, however, he came to peace with her, famously saying, “Madame Bovary: c’est moi.” A model of gorgeous style and perfect characterization, the novel is a testament to how yearning for a higher life both elevates and destroys us.

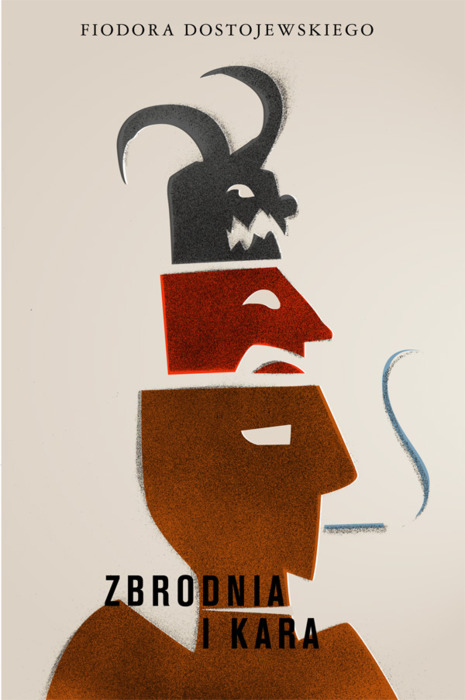

4. Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky (1866). In the peak heat of a St. Petersburg summer, an erstwhile university student, Raskolnikov, commits literature’s most famous fictional crime, bludgeoning a pawnbroker and her sister with an axe. What follows is a psychological chess match between Raskolnikov and a wily detective that moves toward a form of redemption for our antihero. Relentlessly philosophical and psychological, Crime and Punishment tackles freedom and strength, suffering and madness, illness and fate, and the pressures of the modern urban world on the soul, while asking if “great men” have license to forge their own moral codes.

4. Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky (1866). In the peak heat of a St. Petersburg summer, an erstwhile university student, Raskolnikov, commits literature’s most famous fictional crime, bludgeoning a pawnbroker and her sister with an axe. What follows is a psychological chess match between Raskolnikov and a wily detective that moves toward a form of redemption for our antihero. Relentlessly philosophical and psychological, Crime and Punishment tackles freedom and strength, suffering and madness, illness and fate, and the pressures of the modern urban world on the soul, while asking if “great men” have license to forge their own moral codes.

5. Jude the Obscure by Thomas Hardy (1895). Hardy’s protagonists are souls ahead of their time, who dare to aspire and love in defiance of Victorian class structure and social mores. In this bleak but moving novel, class barriers stymie Jude, a self-educated stonemason and would-be scholar, while convention damns his lover Sue, a pagan protofeminist. The flawed hero and heroine win modern hearts, while the author’s ferocious outcry against legal marriage, established religion, and nature itself, still challenges us today.

5. Jude the Obscure by Thomas Hardy (1895). Hardy’s protagonists are souls ahead of their time, who dare to aspire and love in defiance of Victorian class structure and social mores. In this bleak but moving novel, class barriers stymie Jude, a self-educated stonemason and would-be scholar, while convention damns his lover Sue, a pagan protofeminist. The flawed hero and heroine win modern hearts, while the author’s ferocious outcry against legal marriage, established religion, and nature itself, still challenges us today.

6. Hard Times by Charles Dickens (1854). “Now, what I want is, Facts,” reads the opening of this entertaining melodrama animated by impassioned social protest and indignant satire. In the humorless martinet Gradgrind, who preaches and practices uncompromising logic and efficiency, Dickens lampoons the soulless utilitarianism of Victorian philosopher John Stuart Mill. Such reason has spawned the grimy, industrial city of Coketown —which Dickens contrasts with a traveling circus —and informs the subplot concerning Stephen Blackpool’s inescapable, unhappy marriage (a sour fictionalization of Dickens’s own domestic miseries).

6. Hard Times by Charles Dickens (1854). “Now, what I want is, Facts,” reads the opening of this entertaining melodrama animated by impassioned social protest and indignant satire. In the humorless martinet Gradgrind, who preaches and practices uncompromising logic and efficiency, Dickens lampoons the soulless utilitarianism of Victorian philosopher John Stuart Mill. Such reason has spawned the grimy, industrial city of Coketown —which Dickens contrasts with a traveling circus —and informs the subplot concerning Stephen Blackpool’s inescapable, unhappy marriage (a sour fictionalization of Dickens’s own domestic miseries).

7. The Golden Bowl by Henry James (1904).Great chess players used to test their skills by playing several matches at once. A similar sense of multiple levels and strategies animates James’s final completed novel. An impoverished Italian prince marries the daughter of a fabulously wealthy American art collector, who in turn marries the daughter’s best friend, who was once (unbeknownst to father and daughter) the prince’s lover. James examines one of his signature themes —the terrible vulnerability of love to betrayal —in this vertiginous, psychologically acute work.

7. The Golden Bowl by Henry James (1904).Great chess players used to test their skills by playing several matches at once. A similar sense of multiple levels and strategies animates James’s final completed novel. An impoverished Italian prince marries the daughter of a fabulously wealthy American art collector, who in turn marries the daughter’s best friend, who was once (unbeknownst to father and daughter) the prince’s lover. James examines one of his signature themes —the terrible vulnerability of love to betrayal —in this vertiginous, psychologically acute work.

8. Jacob’s Room by Virginia Woolf (1922). Woolf’s first novel to depart from a linear, traditional style follows Jacob Flanders as he goes through Cambridge, carries on love affairs in London, and travels in Greece. Sitting with a girlfriend, he thinks, “It’s not catastrophes, murders, deaths, diseases, that age and kill us, it’s the way people look and laugh, and run up the steps of omnibuses.” Ultimately, it is catastrophe that kills Jacob, as Woolf suggests war’s devastations through this novel’s final description of Jacob’s empty room.

8. Jacob’s Room by Virginia Woolf (1922). Woolf’s first novel to depart from a linear, traditional style follows Jacob Flanders as he goes through Cambridge, carries on love affairs in London, and travels in Greece. Sitting with a girlfriend, he thinks, “It’s not catastrophes, murders, deaths, diseases, that age and kill us, it’s the way people look and laugh, and run up the steps of omnibuses.” Ultimately, it is catastrophe that kills Jacob, as Woolf suggests war’s devastations through this novel’s final description of Jacob’s empty room.

9. Eugénie Grandet by Honoré de Balzac (1833). Part of Balzac’s almost endless La Comédie humaine, Eugénie Grandet is his masterwork on the virus of greed and miserliness. Felix Grandet, a French millionaire, tyrannizes his family with his frugality, going so far as to personally measure the ingredients for each day’s meals. He dashes the romance between his daughter Eugénie and her penniless cousin Charles, setting in motion a bitterly ironic plot worthy of O. Henry, rendered with Balzac’s characteristic detail.

9. Eugénie Grandet by Honoré de Balzac (1833). Part of Balzac’s almost endless La Comédie humaine, Eugénie Grandet is his masterwork on the virus of greed and miserliness. Felix Grandet, a French millionaire, tyrannizes his family with his frugality, going so far as to personally measure the ingredients for each day’s meals. He dashes the romance between his daughter Eugénie and her penniless cousin Charles, setting in motion a bitterly ironic plot worthy of O. Henry, rendered with Balzac’s characteristic detail.

10. Rabbit Angstrom — Rabbit, Run (1960), Rabbit Redux (1971), Rabbit Is Rich (1981), Rabbit at Rest (1990) — by John Updike. Read as four discrete stories or as a seamless quartet, the Rabbit novels are a tour de force chronicle, critique, and eloquent appreciation of the American white Protestant middle-class male and the swiftly shifting culture around him in the last four decades of the twentieth century. From his feckless youth as a promising high school athlete and unready husband and father in Rabbit, Run; through vulgar affluence, serial infidelity, and guilt as a car dealer in Rabbit Redux; to angry bewilderment over 1970s social upheaval in Rabbit Is Rich, the meaningfully named Rabbit Angstrom gamely tries to keep up with it all, to be a good guy. But the world is too much with, and for, Rabbit, who staggers through literal and metaphorical heart failure before finally falling in Rabbit at Rest.

10. Rabbit Angstrom — Rabbit, Run (1960), Rabbit Redux (1971), Rabbit Is Rich (1981), Rabbit at Rest (1990) — by John Updike. Read as four discrete stories or as a seamless quartet, the Rabbit novels are a tour de force chronicle, critique, and eloquent appreciation of the American white Protestant middle-class male and the swiftly shifting culture around him in the last four decades of the twentieth century. From his feckless youth as a promising high school athlete and unready husband and father in Rabbit, Run; through vulgar affluence, serial infidelity, and guilt as a car dealer in Rabbit Redux; to angry bewilderment over 1970s social upheaval in Rabbit Is Rich, the meaningfully named Rabbit Angstrom gamely tries to keep up with it all, to be a good guy. But the world is too much with, and for, Rabbit, who staggers through literal and metaphorical heart failure before finally falling in Rabbit at Rest.