Author Photo And Bio

1. Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy (1877). Anna’s adulterous love affair with Count Vronsky —which follows an inevitable, devastating road from their dizzyingly erotic first encounter at a ball to Anna’s exile from society and her famous, fearful end —is a masterwork of tragic love. What makes the novel so deeply satisfying, though, is how Tolstoy balances the story of Anna’s passion with a second semiautobiographical story of Levin’s spirituality and domesticity. Levin commits his life to simple human values: his marriage to Kitty, his faith in God, and his farming. Tolstoy enchants us with Anna’s sin, then proceeds to educate us with Levin’s virtue.

1. Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy (1877). Anna’s adulterous love affair with Count Vronsky —which follows an inevitable, devastating road from their dizzyingly erotic first encounter at a ball to Anna’s exile from society and her famous, fearful end —is a masterwork of tragic love. What makes the novel so deeply satisfying, though, is how Tolstoy balances the story of Anna’s passion with a second semiautobiographical story of Levin’s spirituality and domesticity. Levin commits his life to simple human values: his marriage to Kitty, his faith in God, and his farming. Tolstoy enchants us with Anna’s sin, then proceeds to educate us with Levin’s virtue.

2. Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky (1866). In the peak heat of a St. Petersburg summer, an erstwhile university student, Raskolnikov, commits literature’s most famous fictional crime, bludgeoning a pawnbroker and her sister with an axe. What follows is a psychological chess match between Raskolnikov and a wily detective that moves toward a form of redemption for our antihero. Relentlessly philosophical and psychological, Crime and Punishment tackles freedom and strength, suffering and madness, illness and fate, and the pressures of the modern urban world on the soul, while asking if “great men” have license to forge their own moral codes.

2. Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky (1866). In the peak heat of a St. Petersburg summer, an erstwhile university student, Raskolnikov, commits literature’s most famous fictional crime, bludgeoning a pawnbroker and her sister with an axe. What follows is a psychological chess match between Raskolnikov and a wily detective that moves toward a form of redemption for our antihero. Relentlessly philosophical and psychological, Crime and Punishment tackles freedom and strength, suffering and madness, illness and fate, and the pressures of the modern urban world on the soul, while asking if “great men” have license to forge their own moral codes.

3. Moby-Dick by Herman Melville (1851). This sweeping saga of obsession, vanity, and vengeance at sea can be read as a harrowing parable, a gripping adventure story, or a semiscientific chronicle of the whaling industry. No matter, the book rewards patient readers with some of fiction’s most memorable characters, from mad Captain Ahab to the titular white whale that crippled him, from the honorable pagan Queequeg to our insightful narrator/surrogate (“Call me”) Ishmael, to that hell-bent vessel itself, the Pequod.

3. Moby-Dick by Herman Melville (1851). This sweeping saga of obsession, vanity, and vengeance at sea can be read as a harrowing parable, a gripping adventure story, or a semiscientific chronicle of the whaling industry. No matter, the book rewards patient readers with some of fiction’s most memorable characters, from mad Captain Ahab to the titular white whale that crippled him, from the honorable pagan Queequeg to our insightful narrator/surrogate (“Call me”) Ishmael, to that hell-bent vessel itself, the Pequod.

4. The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner (1929). A modernist classic of Old South decay, this novel circles the travails of the Compson family from four different narrative perspectives. All are haunted by the figure of Caddy, the only daughter, whom Faulkner described as “a beautiful and tragic little girl.” Surrounding the trials of the family itself are the usual Faulkner suspects: alcoholism, suicide, racism, religion, money, and violence both seen and unseen. In the experimental style of the book, Quentin Compson summarizes the confused honor and tragedy that Faulkner relentlessly evokes: “theres a curse on us its not our fault is it our fault.”

4. The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner (1929). A modernist classic of Old South decay, this novel circles the travails of the Compson family from four different narrative perspectives. All are haunted by the figure of Caddy, the only daughter, whom Faulkner described as “a beautiful and tragic little girl.” Surrounding the trials of the family itself are the usual Faulkner suspects: alcoholism, suicide, racism, religion, money, and violence both seen and unseen. In the experimental style of the book, Quentin Compson summarizes the confused honor and tragedy that Faulkner relentlessly evokes: “theres a curse on us its not our fault is it our fault.”

5. One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez (1967). Widely considered the most popular work in Spanish since Don Quixote, this novel —part fantasy, part social history of Colombia — sparked fiction’s “Latin boom” and the popularization of magic realism. Over a century that seems to move backward and forward simultaneously, the forgotten and offhandedly magical village of Macondo — home to a Faulknerian plethora of incest, floods, massacres, civil wars, dreamers, prudes, and prostitutes — loses its Edenic innocence as it is increasingly exposed to civilization.

5. One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez (1967). Widely considered the most popular work in Spanish since Don Quixote, this novel —part fantasy, part social history of Colombia — sparked fiction’s “Latin boom” and the popularization of magic realism. Over a century that seems to move backward and forward simultaneously, the forgotten and offhandedly magical village of Macondo — home to a Faulknerian plethora of incest, floods, massacres, civil wars, dreamers, prudes, and prostitutes — loses its Edenic innocence as it is increasingly exposed to civilization.

6. Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen (1813). “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife,” reads this novel’s famous opening line. This matching of wife to single man —or good fortune —makes up the plot of perhaps the happiest, smartest romance ever written. Austen’s genius was to make Elizabeth Bennet a reluctant, sometimes crabby equal to her Mr. Darcy, making Pride and Prejudice as much a battle of wits as it is a love story.

6. Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen (1813). “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife,” reads this novel’s famous opening line. This matching of wife to single man —or good fortune —makes up the plot of perhaps the happiest, smartest romance ever written. Austen’s genius was to make Elizabeth Bennet a reluctant, sometimes crabby equal to her Mr. Darcy, making Pride and Prejudice as much a battle of wits as it is a love story.

7. Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert (1857). Of the many nineteenth-century novels about adulteresses, only Madame Bovary features a heroine frankly detested by her author. Flaubert battled for five years to complete his meticulous portrait of extramarital romance in the French provinces, and he complained endlessly in letters about his love-starved main character — so inferior, he felt, to himself. In the end, however, he came to peace with her, famously saying, “Madame Bovary: c’est moi.” A model of gorgeous style and perfect characterization, the novel is a testament to how yearning for a higher life both elevates and destroys us.

7. Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert (1857). Of the many nineteenth-century novels about adulteresses, only Madame Bovary features a heroine frankly detested by her author. Flaubert battled for five years to complete his meticulous portrait of extramarital romance in the French provinces, and he complained endlessly in letters about his love-starved main character — so inferior, he felt, to himself. In the end, however, he came to peace with her, famously saying, “Madame Bovary: c’est moi.” A model of gorgeous style and perfect characterization, the novel is a testament to how yearning for a higher life both elevates and destroys us.

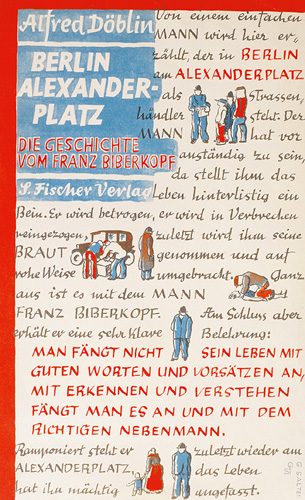

8. Berlin Alexanderplatz by Alfred Döblin (1929).

8. Berlin Alexanderplatz by Alfred Döblin (1929).

9. To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf (1927). The Ramsays and their eight children vacation with an assortment of scholarly and artistic houseguests by the Scottish seaside. Mainly set on two days ten years apart, the novel describes the loss, love, and disagreements of family life while reaching toward the bigger question—“What is the meaning of life?”—that Woolf addresses in meticulously crafted, modernist prose that is impressionistic without being vague or sterile.

9. To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf (1927). The Ramsays and their eight children vacation with an assortment of scholarly and artistic houseguests by the Scottish seaside. Mainly set on two days ten years apart, the novel describes the loss, love, and disagreements of family life while reaching toward the bigger question—“What is the meaning of life?”—that Woolf addresses in meticulously crafted, modernist prose that is impressionistic without being vague or sterile.

10. In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust (1913–27). It’s about time. No, really. This seven-volume, three-thousand-page work is only superficially a mordant critique of French (mostly high) society in the belle époque. Both as author and as “Marcel,” the first-person narrator whose childhood memories are evoked by a crumbling madeleine cookie, Proust asks some of the same questions Einstein did about our notions of time and memory. As we follow the affairs, the badinage, and the betrayals of dozens of characters over the years, time is the highway and memory the driver.

10. In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust (1913–27). It’s about time. No, really. This seven-volume, three-thousand-page work is only superficially a mordant critique of French (mostly high) society in the belle époque. Both as author and as “Marcel,” the first-person narrator whose childhood memories are evoked by a crumbling madeleine cookie, Proust asks some of the same questions Einstein did about our notions of time and memory. As we follow the affairs, the badinage, and the betrayals of dozens of characters over the years, time is the highway and memory the driver.