Author Photo And Bio

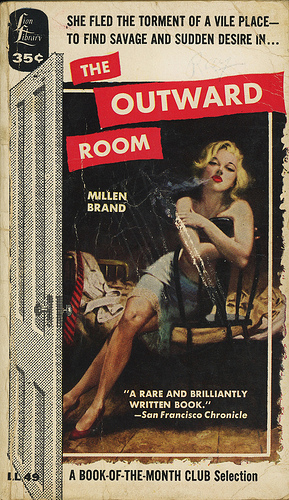

1. The Outward Room by Millen Brand (1937). Also a poet, Brand wrote sensitively about mental illness when the topic was still taboo. This novel tells the story of a woman who escapes from a mental institution and tries to adjust to “normal” life on the “outside.”

1. The Outward Room by Millen Brand (1937). Also a poet, Brand wrote sensitively about mental illness when the topic was still taboo. This novel tells the story of a woman who escapes from a mental institution and tries to adjust to “normal” life on the “outside.”

2. The Professor’s House by Willa Cather (1925). The professor’s house was “almost as ugly as it is possible for a house to be.” Now it has been dismantled. Yet the house, a symbol of the past, keeps beckoning Godfrey St. Peter, a professor in his mid-fifties whose outward success at work and home mask a passionless heart. “Theoretically he knew that life is possible, may be even pleasant, without joy. . . . But it had never occurred to him that he might have to live like that.”

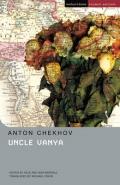

3. Uncle Vanya by Anton Chekhov (1895). Chekhov helped transform the theater through his pioneering use of indirect action —the gunshot fired offstage —and his ability to develop themes not just through dialogue but by creating a mood or atmosphere on stage. He was also a master of characterization. These skills are apparent in this wonderfully complex play, set on an estate in nineteenth-century Russia, which details the relationships among family members who look back on their lives with regret.

3. Uncle Vanya by Anton Chekhov (1895). Chekhov helped transform the theater through his pioneering use of indirect action —the gunshot fired offstage —and his ability to develop themes not just through dialogue but by creating a mood or atmosphere on stage. He was also a master of characterization. These skills are apparent in this wonderfully complex play, set on an estate in nineteenth-century Russia, which details the relationships among family members who look back on their lives with regret.

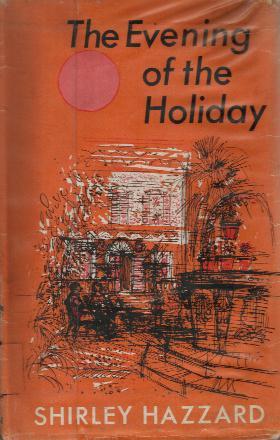

4. The Evening of the Holiday by Shirley Hazzard (1966). Over the course of a festive summer in the Italian countryside, Sophie, who is half English and half Italian, has an affair with Tancredi, an Italian who is separated from his wife and family. Hazzard’s first novel displays the talents and interests that mark her career: luminous prose, the tension between desire and morality, the necessity of choice, and the inevitability of endings.

4. The Evening of the Holiday by Shirley Hazzard (1966). Over the course of a festive summer in the Italian countryside, Sophie, who is half English and half Italian, has an affair with Tancredi, an Italian who is separated from his wife and family. Hazzard’s first novel displays the talents and interests that mark her career: luminous prose, the tension between desire and morality, the necessity of choice, and the inevitability of endings.

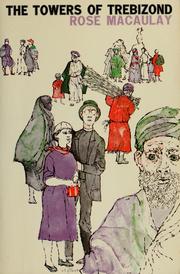

5. The Towers of Trebizond by Rose Macaulay (1956). In the tradition of novels satirizing encounters between eccentric British characters and foreign cultures, Macaulay follows the efforts of four travelers to improve women’s rights, and spread the blessings of the Anglican church, in Turkey. The novel’s first half brims with sharp comic insights. The second half is far more meditative as it focuses on the character Laurie —a church-goer conducting an adulterous affair —who suffers a crisis of faith that becomes a profound spiritual journey.

5. The Towers of Trebizond by Rose Macaulay (1956). In the tradition of novels satirizing encounters between eccentric British characters and foreign cultures, Macaulay follows the efforts of four travelers to improve women’s rights, and spread the blessings of the Anglican church, in Turkey. The novel’s first half brims with sharp comic insights. The second half is far more meditative as it focuses on the character Laurie —a church-goer conducting an adulterous affair —who suffers a crisis of faith that becomes a profound spiritual journey.

6. The Chateau by William Maxwell (1961). Plus ça change: Harold and Barbara Rhodes, a young American couple, expect smiles and bouquets from their liberated hosts as they vacation in France soon after the end of World War II. Instead, they find —surprise!—European chilliness and inscrutability. While this novel’s situation comes straight from Henry James, its language and sensibility —deep empathy and a sense of lost worlds that is not the least bit nostalgic —is pure Maxwell.

6. The Chateau by William Maxwell (1961). Plus ça change: Harold and Barbara Rhodes, a young American couple, expect smiles and bouquets from their liberated hosts as they vacation in France soon after the end of World War II. Instead, they find —surprise!—European chilliness and inscrutability. While this novel’s situation comes straight from Henry James, its language and sensibility —deep empathy and a sense of lost worlds that is not the least bit nostalgic —is pure Maxwell.

7. Quartet in Autumn by Barbara Pym (1977). Barbara Pym’s characters live in the margins of mid-twentieth-century English life, squirreled away in rooming houses, dead-end office jobs, and ever-shrinking church congregations. Her peculiar genius is to make these unpromising creatures the centerpieces of her work. With the acute, unflinching eye and dry sense of humor that invite comparison to Jane Austen, “Quartet in Autumn” follows four aging office workers in their dance with retirement, a changing society, and ultimate mortality.

7. Quartet in Autumn by Barbara Pym (1977). Barbara Pym’s characters live in the margins of mid-twentieth-century English life, squirreled away in rooming houses, dead-end office jobs, and ever-shrinking church congregations. Her peculiar genius is to make these unpromising creatures the centerpieces of her work. With the acute, unflinching eye and dry sense of humor that invite comparison to Jane Austen, “Quartet in Autumn” follows four aging office workers in their dance with retirement, a changing society, and ultimate mortality.

8. Light Years by James Salter (1975). This compact novel offers achingly perceptive scenes from a marriage during a twenty-year period. As Viri and Nedra Berland host dinner parties, shop in New York City, summer on Long Island, and take on lovers, they experience happiness, bereavement, isolation, and divorce. Through this portrait, Salter suggests that each person’s life is “mysterious, it is like a forest; from far off it . . . can be comprehended, described, but closer it begins to separate, to break into light and shadow, the density blinds one.”

8. Light Years by James Salter (1975). This compact novel offers achingly perceptive scenes from a marriage during a twenty-year period. As Viri and Nedra Berland host dinner parties, shop in New York City, summer on Long Island, and take on lovers, they experience happiness, bereavement, isolation, and divorce. Through this portrait, Salter suggests that each person’s life is “mysterious, it is like a forest; from far off it . . . can be comprehended, described, but closer it begins to separate, to break into light and shadow, the density blinds one.”

9. What’s for Dinner? by James Schuyler (1978). Best known as a poet, Schuyler brings his eye for intimate details to this quirky comedy about three families in suburban Long Island. As his characters deal with rowdy children, alcoholism, and loneliness, Schuyler subtly explores the forces that tear people apart and bring them back together.

9. What’s for Dinner? by James Schuyler (1978). Best known as a poet, Schuyler brings his eye for intimate details to this quirky comedy about three families in suburban Long Island. As his characters deal with rowdy children, alcoholism, and loneliness, Schuyler subtly explores the forces that tear people apart and bring them back together.

10. A Voice Through a Cloud by Denton Welch (1950). “Though Welch has the abilities of a novelist,” John Updike wrote, “misfortune made him a kind of prophet.” In this autobiographical novel, Welch describes the bicycle accident that left him partially paralyzed at age twenty, the painful treatments he suffered, and the loneliness he endured. Filled with acute observations and revealing self-analysis, this intimate novel offers a wrenching portrait of despair.

10. A Voice Through a Cloud by Denton Welch (1950). “Though Welch has the abilities of a novelist,” John Updike wrote, “misfortune made him a kind of prophet.” In this autobiographical novel, Welch describes the bicycle accident that left him partially paralyzed at age twenty, the painful treatments he suffered, and the loneliness he endured. Filled with acute observations and revealing self-analysis, this intimate novel offers a wrenching portrait of despair.