Author Photo And Bio

1. The Catcher in the Rye by J. D. Salinger (1951). After being dismissed from another prep school, Holden Caulfield —whose slangy, intimate narration defines this novel —has a series of misadventures in Manhattan before going home for Christmas. Haunted by the death of brother Allie, he wants what he cannot have —to snare the elusive Jane Gallagher, to run away with his sister Phoebe, to “catch” innocent youths before they fall into the “phony” world of adults. A timeless voice of adolescent rage and assurance, Holden may rank highest in the pantheon of antiestablishment heroes.

1. The Catcher in the Rye by J. D. Salinger (1951). After being dismissed from another prep school, Holden Caulfield —whose slangy, intimate narration defines this novel —has a series of misadventures in Manhattan before going home for Christmas. Haunted by the death of brother Allie, he wants what he cannot have —to snare the elusive Jane Gallagher, to run away with his sister Phoebe, to “catch” innocent youths before they fall into the “phony” world of adults. A timeless voice of adolescent rage and assurance, Holden may rank highest in the pantheon of antiestablishment heroes.

2. Native Son by Richard Wright (1945). Set in Chicago in the 1930s, this novel tells the story of Bigger Thomas, an African American twisted and trapped by penury and racism. Bigger is on his way out of poverty when he accidently murders his employer’s daughter, a white woman. In this highly charged, deeply influential novel, Wright portrays a black man squeezed by crushing circumstances who comes to understand his own identity.

2. Native Son by Richard Wright (1945). Set in Chicago in the 1930s, this novel tells the story of Bigger Thomas, an African American twisted and trapped by penury and racism. Bigger is on his way out of poverty when he accidently murders his employer’s daughter, a white woman. In this highly charged, deeply influential novel, Wright portrays a black man squeezed by crushing circumstances who comes to understand his own identity.

3. Song of Solomon by Toni Morrison (1977). As witty and agile as a folk tale, psychologically acute and colorfully drawn, this novel blends elements of fable and the contemporary novel to depict a young man’s search for identity. In her protagonist, Macon Dead, Morrison created one of her greatest characters, and his reluctant coming of age becomes a comic, mythic, eloquent analysis of self-knowledge and community —how those things can save us, and what happens when they do not.

3. Song of Solomon by Toni Morrison (1977). As witty and agile as a folk tale, psychologically acute and colorfully drawn, this novel blends elements of fable and the contemporary novel to depict a young man’s search for identity. In her protagonist, Macon Dead, Morrison created one of her greatest characters, and his reluctant coming of age becomes a comic, mythic, eloquent analysis of self-knowledge and community —how those things can save us, and what happens when they do not.

4. Beloved by Toni Morrison (1987). It’s a choice no mother should have to make. In 1856, escaped slave Margaret Garner decided to kill her infant daughter rather than return her to slavery. Her desperate act created a national sensation. Where Garner’s true-life drama ends, Beloved begins. In this Pulitzer Prize–winning novel, the murdered child, Beloved, returns from the grave years later to haunt her mother Sethe. Aided by her daughter Denver and lover Paul D, Sethe confronts the all-consuming guilt precipitated by the ghostly embodiment of her dead child. Rendered in poetic language, Beloved is a stunning indictment of slavery “full of baby’s venom.”

4. Beloved by Toni Morrison (1987). It’s a choice no mother should have to make. In 1856, escaped slave Margaret Garner decided to kill her infant daughter rather than return her to slavery. Her desperate act created a national sensation. Where Garner’s true-life drama ends, Beloved begins. In this Pulitzer Prize–winning novel, the murdered child, Beloved, returns from the grave years later to haunt her mother Sethe. Aided by her daughter Denver and lover Paul D, Sethe confronts the all-consuming guilt precipitated by the ghostly embodiment of her dead child. Rendered in poetic language, Beloved is a stunning indictment of slavery “full of baby’s venom.”

5. Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison (1952). This modernist novel follows the bizarre, often surreal adventures of an unnamed narrator, a black man, whose identity becomes a battleground in racially divided America. Expected to be submissive and obedient in the South, he must decipher the often contradictory rules whites set for a black man’s behavior. Traveling north to Harlem, he meets white leaders intent on controlling and manipulating him. Desperate to seize control of his life, he imitates Dostoevsky’s underground man, escaping down a manhole where he vows to remain until he can define himself. The book’s famous last line, “Who knows, but that on the lower frequencies I speak for you,” suggests how it transcends race to tell a universal story of the quest for self-determination.

5. Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison (1952). This modernist novel follows the bizarre, often surreal adventures of an unnamed narrator, a black man, whose identity becomes a battleground in racially divided America. Expected to be submissive and obedient in the South, he must decipher the often contradictory rules whites set for a black man’s behavior. Traveling north to Harlem, he meets white leaders intent on controlling and manipulating him. Desperate to seize control of his life, he imitates Dostoevsky’s underground man, escaping down a manhole where he vows to remain until he can define himself. The book’s famous last line, “Who knows, but that on the lower frequencies I speak for you,” suggests how it transcends race to tell a universal story of the quest for self-determination.

6. Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert (1857). Of the many nineteenth-century novels about adulteresses, only Madame Bovary features a heroine frankly detested by her author. Flaubert battled for five years to complete his meticulous portrait of extramarital romance in the French provinces, and he complained endlessly in letters about his love-starved main character — so inferior, he felt, to himself. In the end, however, he came to peace with her, famously saying, “Madame Bovary: c’est moi.” A model of gorgeous style and perfect characterization, the novel is a testament to how yearning for a higher life both elevates and destroys us.

6. Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert (1857). Of the many nineteenth-century novels about adulteresses, only Madame Bovary features a heroine frankly detested by her author. Flaubert battled for five years to complete his meticulous portrait of extramarital romance in the French provinces, and he complained endlessly in letters about his love-starved main character — so inferior, he felt, to himself. In the end, however, he came to peace with her, famously saying, “Madame Bovary: c’est moi.” A model of gorgeous style and perfect characterization, the novel is a testament to how yearning for a higher life both elevates and destroys us.

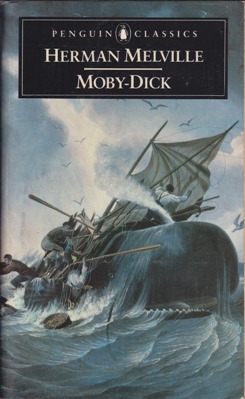

7. Moby-Dick by Herman Melville (1851). This sweeping saga of obsession, vanity, and vengeance at sea can be read as a harrowing parable, a gripping adventure story, or a semiscientific chronicle of the whaling industry. No matter, the book rewards patient readers with some of fiction’s most memorable characters, from mad Captain Ahab to the titular white whale that crippled him, from the honorable pagan Queequeg to our insightful narrator/surrogate (“Call me”) Ishmael, to that hell-bent vessel itself, the Pequod.

7. Moby-Dick by Herman Melville (1851). This sweeping saga of obsession, vanity, and vengeance at sea can be read as a harrowing parable, a gripping adventure story, or a semiscientific chronicle of the whaling industry. No matter, the book rewards patient readers with some of fiction’s most memorable characters, from mad Captain Ahab to the titular white whale that crippled him, from the honorable pagan Queequeg to our insightful narrator/surrogate (“Call me”) Ishmael, to that hell-bent vessel itself, the Pequod.

8. The Color Purple by Alice Walker (1982). As if being black weren’t hard enough, Walker’s Pulitzer Prize– winning novel shows how bad life can get if you’re also a woman. Wondrously, Walker gives voice to the unlikeliest of heroes —a barely literate teenager named Celie who writes letters to God as an escape from life with her monstrous stepfather. After raping and impregnating her, he forces her to marry Mr., a cruel older man. Hope comes in the form of Shug, Mr.’s lover, and together the two women begin to loosen the shackles of race and gender.

8. The Color Purple by Alice Walker (1982). As if being black weren’t hard enough, Walker’s Pulitzer Prize– winning novel shows how bad life can get if you’re also a woman. Wondrously, Walker gives voice to the unlikeliest of heroes —a barely literate teenager named Celie who writes letters to God as an escape from life with her monstrous stepfather. After raping and impregnating her, he forces her to marry Mr., a cruel older man. Hope comes in the form of Shug, Mr.’s lover, and together the two women begin to loosen the shackles of race and gender.

9. An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser (1925).Clyde Griffiths wants to be more than just the son of a Midwestern preacher. Leaving home, he follows a path toward the American Dream that is littered with greed, adultery, and hypocrisy. The brass ring seems close when he wins a wealthy girl’s love, but then very far away when a factory girl he impregnated demands that he marry her. In this disquieting social novel, Clyde faces a moral dilemma that reveals the corruption of his soul and the materialistic culture that seduces him.

9. An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser (1925).Clyde Griffiths wants to be more than just the son of a Midwestern preacher. Leaving home, he follows a path toward the American Dream that is littered with greed, adultery, and hypocrisy. The brass ring seems close when he wins a wealthy girl’s love, but then very far away when a factory girl he impregnated demands that he marry her. In this disquieting social novel, Clyde faces a moral dilemma that reveals the corruption of his soul and the materialistic culture that seduces him.

10. Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy (1877). Anna’s adulterous love affair with Count Vronsky —which follows an inevitable, devastating road from their dizzyingly erotic first encounter at a ball to Anna’s exile from society and her famous, fearful end —is a masterwork of tragic love. What makes the novel so deeply satisfying, though, is how Tolstoy balances the story of Anna’s passion with a second semiautobiographical story of Levin’s spirituality and domesticity. Levin commits his life to simple human values: his marriage to Kitty, his faith in God, and his farming. Tolstoy enchants us with Anna’s sin, then proceeds to educate us with Levin’s virtue.

10. Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy (1877). Anna’s adulterous love affair with Count Vronsky —which follows an inevitable, devastating road from their dizzyingly erotic first encounter at a ball to Anna’s exile from society and her famous, fearful end —is a masterwork of tragic love. What makes the novel so deeply satisfying, though, is how Tolstoy balances the story of Anna’s passion with a second semiautobiographical story of Levin’s spirituality and domesticity. Levin commits his life to simple human values: his marriage to Kitty, his faith in God, and his farming. Tolstoy enchants us with Anna’s sin, then proceeds to educate us with Levin’s virtue.