Author Photo And Bio

1. The Time of the Doves by Mercè Rodoreda (1962). The author uses a stream of consciousness technique to describe the fraught experiences and often choked-off feelings of a Spanish shopkeeper during the 1930s and 1940s as her nation becomes gripped by civil war and fascism.

1. The Time of the Doves by Mercè Rodoreda (1962). The author uses a stream of consciousness technique to describe the fraught experiences and often choked-off feelings of a Spanish shopkeeper during the 1930s and 1940s as her nation becomes gripped by civil war and fascism.

2. The Ten Thousand Things by Maria Dermout (1955). Dermout was sixty-seven years old when she debuted with this semiautobiographical novel about a Dutch woman named Felicia raising her son in the Spice Islands of Indonesia. Felicia has a keen appreciation for the beauty and mystery of this lush and exotic world where spirits hover; she describes pearls as “tears of the sea” while telling her boy the ten thousand things that make the island. Her love of life and nature is challenged by violence and murder that bring sadness and summon the courage of resilience.

2. The Ten Thousand Things by Maria Dermout (1955). Dermout was sixty-seven years old when she debuted with this semiautobiographical novel about a Dutch woman named Felicia raising her son in the Spice Islands of Indonesia. Felicia has a keen appreciation for the beauty and mystery of this lush and exotic world where spirits hover; she describes pearls as “tears of the sea” while telling her boy the ten thousand things that make the island. Her love of life and nature is challenged by violence and murder that bring sadness and summon the courage of resilience.

3. Stones for Ibarra by Harriet Doerr (1984). Seeking renewal, Richard and Sara Everton leave San Francisco for a remote village in Mexico. There they hope to reopen Richard’s grandfather’s old mine, to “patch the present on to the past. To find out if there was still copper underground and how much the rest of it was true, the width of the sky, the depth of the stars, the air like new wine, the harsh noons and long, slow dusks.” In lovely, spare prose, this National Book Award–winning novel describes the Evertons’ flowering relationships with the vividly drawn people of Ibarra and the deadly illness that hovers over their happiness.

3. Stones for Ibarra by Harriet Doerr (1984). Seeking renewal, Richard and Sara Everton leave San Francisco for a remote village in Mexico. There they hope to reopen Richard’s grandfather’s old mine, to “patch the present on to the past. To find out if there was still copper underground and how much the rest of it was true, the width of the sky, the depth of the stars, the air like new wine, the harsh noons and long, slow dusks.” In lovely, spare prose, this National Book Award–winning novel describes the Evertons’ flowering relationships with the vividly drawn people of Ibarra and the deadly illness that hovers over their happiness.

4. The Burning Plain and Other Stories by Juan Rulfo (1953). Like Ernest Hemingway, Rulfo found men who are shaped by violence too fascinating to judge or condemn. Set in the period around the Mexican Revolution, his short stories use pared down prose to portray peasants who are seized sometimes by historical forces and given the opportunity to create and destroy on a mass scale. More usually, they decimate or are decimated in miserable increments.

4. The Burning Plain and Other Stories by Juan Rulfo (1953). Like Ernest Hemingway, Rulfo found men who are shaped by violence too fascinating to judge or condemn. Set in the period around the Mexican Revolution, his short stories use pared down prose to portray peasants who are seized sometimes by historical forces and given the opportunity to create and destroy on a mass scale. More usually, they decimate or are decimated in miserable increments.

5. Good Morning, Midnight by Jean Rhys (1939). On hell’s short bookshelf of great writing about alcohol, this novel is narrated by Sasha Jansen, a semi-writer at loose ends who is planning a permanent swan dive into the bottle. While Virginia Woolf thought women needed a room of their own for creative work, Jansen believes “a room is a place where you hide from the wolves outside.” Jansen’s fugue through 1930s Paris, while pursued by age, disapproving bartenders, and a stubborn gigolo, is a café blues song: stylish and haunting.

5. Good Morning, Midnight by Jean Rhys (1939). On hell’s short bookshelf of great writing about alcohol, this novel is narrated by Sasha Jansen, a semi-writer at loose ends who is planning a permanent swan dive into the bottle. While Virginia Woolf thought women needed a room of their own for creative work, Jansen believes “a room is a place where you hide from the wolves outside.” Jansen’s fugue through 1930s Paris, while pursued by age, disapproving bartenders, and a stubborn gigolo, is a café blues song: stylish and haunting.

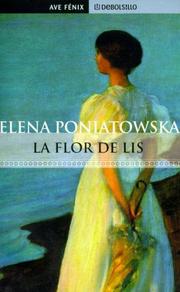

6. La Flor de Lis by Elena Poniatowska (1988). (See below.)

6. La Flor de Lis by Elena Poniatowska (1988). (See below.)

7. Borderlands/La Frontera by Gloria Anzaldúa (1999). The author uses poetry and prose —mythology, history, memoir —in this passionate account of two types of borders. The first is the physical one between Texas and Mexico. The second is psychological, mapping borderlands defined by sex, race, class, culture, and religion. She is particularly interested in intersections, “where the space between two individuals shrinks with intimacy.”

7. Borderlands/La Frontera by Gloria Anzaldúa (1999). The author uses poetry and prose —mythology, history, memoir —in this passionate account of two types of borders. The first is the physical one between Texas and Mexico. The second is psychological, mapping borderlands defined by sex, race, class, culture, and religion. She is particularly interested in intersections, “where the space between two individuals shrinks with intimacy.”

8. The Book of Embraces by Eduardo Galeano (1989). “Why does one write, if not to put one’s pieces together?” the Uruguayan author asks in this work of “literary collage.” Through scores of brief pieces both whimsical and earnest, Galeano recalls his personal life —including years of political exile and his heart attack —and topics large and small, ranging from his wife’s dreams to the art of graffiti to repression in Latin America. Together with his imaginative drawings, they render a vivid portrait of this compassionate and visionary author’s life and mind.

9. Dreamtigers by Jorge Luis Borges (1964). Borges called this “straggling collection” of tiny prose pieces and poems his most personal book. It contains meditations on the usual Borges themes: doubles, time as a fiction, the incursion of literature on reality. Its famous piece, Borges and I, is the most compact confession in all literature, as the real Borges seeks to disentangle himself from the writer Borges, concluding: “I do not know which of us two is writing this page.” Such abysses of Escher-like perspective mark this Argentinianunique style.

9. Dreamtigers by Jorge Luis Borges (1964). Borges called this “straggling collection” of tiny prose pieces and poems his most personal book. It contains meditations on the usual Borges themes: doubles, time as a fiction, the incursion of literature on reality. Its famous piece, Borges and I, is the most compact confession in all literature, as the real Borges seeks to disentangle himself from the writer Borges, concluding: “I do not know which of us two is writing this page.” Such abysses of Escher-like perspective mark this Argentinianunique style.

10. Maud Martha by Gwendolyn Brooks (1953). Brooks is best known for her poetry about African American life in Chicago, winning the Pulitzer Prize for Annie Allen (1949). In Maud Martha, Brooks switches to prose fiction, recounting the stages of a young woman’s life during the 1930s and 1940s. The story follows Maud as she struggles with school, work, marriage, childbirth, and motherhood against the all-pervasive backdrop of racism and sexism. Told with unflinching honesty, sensitivity, and humor, Maud Martha is also a work of lyrical beauty.

10. Maud Martha by Gwendolyn Brooks (1953). Brooks is best known for her poetry about African American life in Chicago, winning the Pulitzer Prize for Annie Allen (1949). In Maud Martha, Brooks switches to prose fiction, recounting the stages of a young woman’s life during the 1930s and 1940s. The story follows Maud as she struggles with school, work, marriage, childbirth, and motherhood against the all-pervasive backdrop of racism and sexism. Told with unflinching honesty, sensitivity, and humor, Maud Martha is also a work of lyrical beauty.

Appreciation of Elena Poniatowska’s La Flor de Lis by Sandra Cisneros

The little hand serving me coffee is also the hand that wrote the exquisite novel La Flor de Lis (1988). It seems absurd a writer of such worth should bother serving coffee to anyone, but it’s precisely this humility, this willingness to serve others, whether it be coffee, or novels, or testimonies, or tamales, that makes Elena Poniatowska a writer as well loved by cab drivers as by professors. The title alludes to France, but if you’re hip to Mexico City, you’ll know La Flor de Lis is also the famous tamale restaurant in la colonia Condesa.

La Flor de Lis is a love story about mother and motherland, about love of México lindo y querido (pretty and best), a culture where mothers are revered as goddesses, and a goddess, la Virgen de Guadalupe, is revered because she is “the” mother.

It’s a fairy tale told in reverse. Daughters of royalty flee France under siege from World War Il, and in the course of their childhood and adolescence in Mexico, we witness the discovery of what it means to belong to a culture, what it means to fall in love, and what, after all, it means to be a woman, because the story is steeped in the body of a woman, in the body of that country.

Nowhere else have I read anyone describe the joy of scrubbing a courtyard with a bucket of suds and a broom. But it’s el zócalo, the central plaza of Mexico City that the narrator wants to scrub out of puro amor. And that ultimately sums up how a writer like Elenita became Elena Poniatowska. What we do for love, after all, is the greatest work we can do.