Author Photo And Bio

1. Ulysses by James Joyce (1922). Filled with convoluted plotting, scrambled syntax, puns, neologisms, and arcane mythological allusions, Ulysses recounts the misadventures of schlubby Dublin advertising salesman Leopold Bloom on a single day, June 16, 1904. As Everyman Bloom and a host of other characters act out, on a banal and quotidian scale, the major episodes of Homer’s Odyssey —including encounters with modern-day sirens and a Cyclops —Joyce’s bawdy mock-epic suggests the improbability, perhaps even the pointlessness, of heroism in the modern age.

1. Ulysses by James Joyce (1922). Filled with convoluted plotting, scrambled syntax, puns, neologisms, and arcane mythological allusions, Ulysses recounts the misadventures of schlubby Dublin advertising salesman Leopold Bloom on a single day, June 16, 1904. As Everyman Bloom and a host of other characters act out, on a banal and quotidian scale, the major episodes of Homer’s Odyssey —including encounters with modern-day sirens and a Cyclops —Joyce’s bawdy mock-epic suggests the improbability, perhaps even the pointlessness, of heroism in the modern age.

2. Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov (1955). “Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul.” So begins the Russian master’s infamous novel about Humbert Humbert, a middle-aged man who falls madly, obsessively in love with a twelve-year-old “nymphet,” Dolores Haze. So he marries the girl’s mother. When she dies he becomes Lolita’s father. As Humbert describes their car trip —a twisted mockery of the American road novel —Nabokov depicts love, power, and obsession in audacious, shockingly funny language.

2. Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov (1955). “Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul.” So begins the Russian master’s infamous novel about Humbert Humbert, a middle-aged man who falls madly, obsessively in love with a twelve-year-old “nymphet,” Dolores Haze. So he marries the girl’s mother. When she dies he becomes Lolita’s father. As Humbert describes their car trip —a twisted mockery of the American road novel —Nabokov depicts love, power, and obsession in audacious, shockingly funny language.

3. Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov (1962). “It is the commentator who has the last word,” claims Charles Kinbote in this novel masquerading as literary criticism. The text of the book includes a 999-line poem by the murdered American poet John Shade and a line-by-line commentary by Kinbote, a scholar from the country of Zembla. Nabokov even provides an index to this playful, provocative story of poetry, interpretation, identity, and madness, which is full to bursting with allusions, tricks, and the author’s inimitable wordplay.

3. Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov (1962). “It is the commentator who has the last word,” claims Charles Kinbote in this novel masquerading as literary criticism. The text of the book includes a 999-line poem by the murdered American poet John Shade and a line-by-line commentary by Kinbote, a scholar from the country of Zembla. Nabokov even provides an index to this playful, provocative story of poetry, interpretation, identity, and madness, which is full to bursting with allusions, tricks, and the author’s inimitable wordplay.

4. Bleak House by Charles Dickens (1853). Dickens is best known for his immense plots that trace every corner of Victorian society, and Bleak House fulfills that expectation to perfection. The plot braids the sentimental tale of an orphan unaware of her scandalous parentage with an ironic and bitterly funny satire of a lawsuit that appears to entail all of London. In doing so, the novel encompasses more than any other Dickens novel, shows the author’s mature skills, and is the only Victorian novel to include an incident of human spontaneous combustion.

4. Bleak House by Charles Dickens (1853). Dickens is best known for his immense plots that trace every corner of Victorian society, and Bleak House fulfills that expectation to perfection. The plot braids the sentimental tale of an orphan unaware of her scandalous parentage with an ironic and bitterly funny satire of a lawsuit that appears to entail all of London. In doing so, the novel encompasses more than any other Dickens novel, shows the author’s mature skills, and is the only Victorian novel to include an incident of human spontaneous combustion.

5. Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert (1857). Of the many nineteenth-century novels about adulteresses, only Madame Bovary features a heroine frankly detested by her author. Flaubert battled for five years to complete his meticulous portrait of extramarital romance in the French provinces, and he complained endlessly in letters about his love-starved main character — so inferior, he felt, to himself. In the end, however, he came to peace with her, famously saying, “Madame Bovary: c’est moi.” A model of gorgeous style and perfect characterization, the novel is a testament to how yearning for a higher life both elevates and destroys us.

5. Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert (1857). Of the many nineteenth-century novels about adulteresses, only Madame Bovary features a heroine frankly detested by her author. Flaubert battled for five years to complete his meticulous portrait of extramarital romance in the French provinces, and he complained endlessly in letters about his love-starved main character — so inferior, he felt, to himself. In the end, however, he came to peace with her, famously saying, “Madame Bovary: c’est moi.” A model of gorgeous style and perfect characterization, the novel is a testament to how yearning for a higher life both elevates and destroys us.

6. To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf (1927). The Ramsays and their eight children vacation with an assortment of scholarly and artistic houseguests by the Scottish seaside. Mainly set on two days ten years apart, the novel describes the loss, love, and disagreements of family life while reaching toward the bigger question—“What is the meaning of life?”—that Woolf addresses in meticulously crafted, modernist prose that is impressionistic without being vague or sterile.

6. To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf (1927). The Ramsays and their eight children vacation with an assortment of scholarly and artistic houseguests by the Scottish seaside. Mainly set on two days ten years apart, the novel describes the loss, love, and disagreements of family life while reaching toward the bigger question—“What is the meaning of life?”—that Woolf addresses in meticulously crafted, modernist prose that is impressionistic without being vague or sterile.

7. Gusev by Anton Chekhov (1860–1904). The son of a freed Russian serf, Anton Chekhov became a doctor who, between the patients he often treated without charge, invented the modern short story. The form had been overdecorated with trick endings and swags of atmosphere. Chekhov freed it to reflect the earnest urgencies of ordinary lives in crises through prose that blended a deeply compassionate imagination with precise description. “He remains a great teacher-healer-sage,” Allan Gurganus observed of Chekhov’s stories, which “continue to haunt, inspire, and baffle.”

7. Gusev by Anton Chekhov (1860–1904). The son of a freed Russian serf, Anton Chekhov became a doctor who, between the patients he often treated without charge, invented the modern short story. The form had been overdecorated with trick endings and swags of atmosphere. Chekhov freed it to reflect the earnest urgencies of ordinary lives in crises through prose that blended a deeply compassionate imagination with precise description. “He remains a great teacher-healer-sage,” Allan Gurganus observed of Chekhov’s stories, which “continue to haunt, inspire, and baffle.”

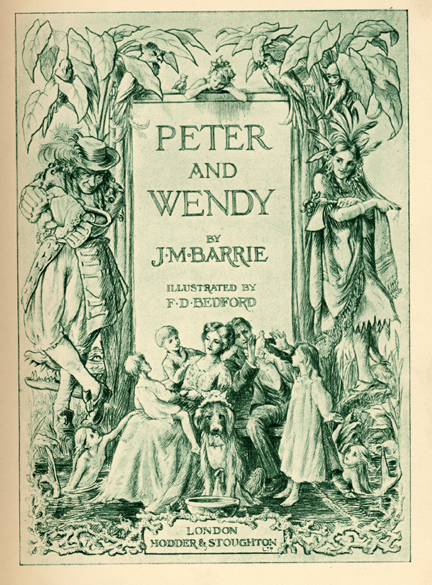

8. Peter Pan by J. M. Barrie (1904). “All children, except one, grow up,” reads the opening line of this swashbuckling tale of that boy, named Peter Pan, who takes the Darling children to Neverland. There they encounter a host of immortal figures, including Tinker Bell and Tiger Lily, the Lost Boys, and Captain Hook, as readers learn that the best hedge against old age is to believe in our imaginations (and fairies). Initially produced as a play, the story was published as a book in 1911 under the title Peter and Wendy.

8. Peter Pan by J. M. Barrie (1904). “All children, except one, grow up,” reads the opening line of this swashbuckling tale of that boy, named Peter Pan, who takes the Darling children to Neverland. There they encounter a host of immortal figures, including Tinker Bell and Tiger Lily, the Lost Boys, and Captain Hook, as readers learn that the best hedge against old age is to believe in our imaginations (and fairies). Initially produced as a play, the story was published as a book in 1911 under the title Peter and Wendy.

9. Dead Souls by Nikolai Gogol (1842). Gogol’s self-proclaimed narrative “poem” follows the comical ambitions of Chichikov, who travels around the country buying the “dead souls” of serfs not yet stricken from the tax rolls. A stinging satire of Russian bureaucracy, social rank, and serfdom, Dead Souls also soars as Gogol’s portrait of “all Russia,” racing on “like a brisk, unbeatable troika” before which “other nations and states step aside to make way.”

9. Dead Souls by Nikolai Gogol (1842). Gogol’s self-proclaimed narrative “poem” follows the comical ambitions of Chichikov, who travels around the country buying the “dead souls” of serfs not yet stricken from the tax rolls. A stinging satire of Russian bureaucracy, social rank, and serfdom, Dead Souls also soars as Gogol’s portrait of “all Russia,” racing on “like a brisk, unbeatable troika” before which “other nations and states step aside to make way.”

10. The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Victor Hugo (1831). Hugo’s grand populist opera stars the cathedral and medieval Paris itself as much as the hunchbacked bell-ringer Quasimodo, whose unrequited love for the gypsy dancer Esmeralda ends very, very badly. The book is far more nineteenth century than fifteenth, brimming with melodrama, anticlericism, and Hugo’s characteristic outrage at social injustice. The novel’s huge popularity in France was instrumental in a neo-Gothic revival there, as well as the preservation of Notre Dame itself.

10. The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Victor Hugo (1831). Hugo’s grand populist opera stars the cathedral and medieval Paris itself as much as the hunchbacked bell-ringer Quasimodo, whose unrequited love for the gypsy dancer Esmeralda ends very, very badly. The book is far more nineteenth century than fifteenth, brimming with melodrama, anticlericism, and Hugo’s characteristic outrage at social injustice. The novel’s huge popularity in France was instrumental in a neo-Gothic revival there, as well as the preservation of Notre Dame itself.