The Third Policeman by Flann O’Brien (composed 1939-40; published 1967).

The Third Policeman by Flann O’Brien (composed 1939-40; published 1967).

Appreciation of Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman by A. L. Kennedy

The Third Policeman is that rare and lovely thing—a truly hallucinatory novel, shot through with fierce logic and intellectual rigor. It is a lyrical, amoral, funny nightmare: the most disciplined and disturbing product of an always interesting writer. Our protagonist is “the poor misfortunate bastard”—a drinker, philosopher, and obsessive bibliophile. His sins grow with him, making a logical progression from book theft to burglary and murder—all this against a heightened version of poor, rural Ireland: a setting layered with absurd but weirdly recognizable detail. He then stumbles into a potentially fatal alternative reality: a haunting, teasing Irish countryside of parlors and winding roads from which it seems impossible to return.

Beneath the music of O’Brien’s prose there is always a savage understanding of our failings, the pressures of poverty, greed, and fear. And there is always the dark humor that both excuses and condemns us. Our hero (who develops an entirely separate soul, called Joe) drifts into a weird landscape of jovially menacing policemen (who may or not may not be bicycles) and of inexplicable objects and mechanisms that operate beneath nature’s skin. His imprisonment and threatened execution seem even more troubling because they are nonsensical, perhaps even kind. Slowly it becomes clear that, among other things, this novel is about hell—a much-deserved, amusing, irrational, and entirely inescapable hell. Because, for O’Brien, hell is not only other people—it is ourselves.

Beyond this, The Third Policeman is genuinely indescribable: a book that holds you like a lovely and accusing dream. Read it and you’ll never forget it. Meet anyone else who has read it and you’ll find yourselves repeating sections of its melodious insanity within moments. Meet anyone who hasn’t read it and you’ll tell them they must. Which will be the truth.

The Time of the Doves

The Time of the Doves The Unbearable Lightness of Being

The Unbearable Lightness of Being The Untouchable

The Untouchable The Woman in the Dunes

The Woman in the Dunes Things Fall Apart

Things Fall Apart 1982, Janine

1982, Janine A Doll’s House

A Doll’s House A Streetcar Named Desire

A Streetcar Named Desire Aesop’s Fables

Aesop’s Fables Buddenbrooks

Buddenbrooks Doctor Faustus

Doctor Faustus Edwin Mullhouse : The Life and Death of an American Writer 1943-1954 by Jeffrey Cartwright

Edwin Mullhouse : The Life and Death of an American Writer 1943-1954 by Jeffrey Cartwright Essays

Essays Henry V

Henry V Howl

Howl Kristin Lavransdatter

Kristin Lavransdatter Life: A User’s Manual

Life: A User’s Manual Mahabharata

Mahabharata Medea

Medea Othello, The Moor of Venice

Othello, The Moor of Venice Plays of Molière

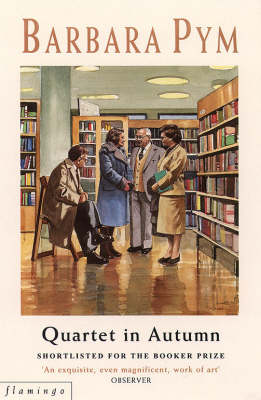

Plays of Molière Quartet in Autumn

Quartet in Autumn Stories of Andre Dubus

Stories of Andre Dubus Sunset Song

Sunset Song